Josef Albers’ Secret Circle

If there’s a form best associated with Josef Albers, it would undoubtedly be the square. His seminal series “Homage to the Square” (started in 1949 and carried out over a 25-year period) features hundreds of color variations of the nested shape in a meticulous study on the interaction of color. He aimed to challenge perception with these paintings, using color relationships to create shifting illusions of depth and space, teaching viewers, in his words, “how to see.” For Albers, the square represented neutrality; it was free of meaning, and thus the perfect canvas to minimize formal variables. Later, he would continue his perceptual experimentation with architectural commissions, turning his attention from color to light and shade, using a similar neutral and rectilinear framework: the brick.

In 1950, Walter Gropius commissioned Albers to create a brick fireplace at Harvard University, which in turn caught the attention of architect and Albers’ Yale colleague King-lui Wu. Wu was working on his first residential project for the Rouse family, and enamored by the brick fireplace at Harvard, requested Albers to design one for the living room of the new house. As associates, the two had been in dialogue about European modernism, color, light, and perception, and saw the fireplace as the perfect project to materialize their mutual interests. In preparation, Albers created several models of brick patterns, which he then photographed in a variety of lighting conditions. The final structure is composed of bricks set at various angles, conveying a sense of motion further enhanced as the brick’s shadows ebb and flow throughout the day. The Rouse fireplace went on to become an architectural marvel, recently gaining new attention at a 2004 Josef and Anni Albers exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Museum. The project and accompanying photographic studies established a strong foundation for a stint of successful collaborations between Albers and Wu in the years to follow.

Rouse fireplace designed by Josef Albers, 1954

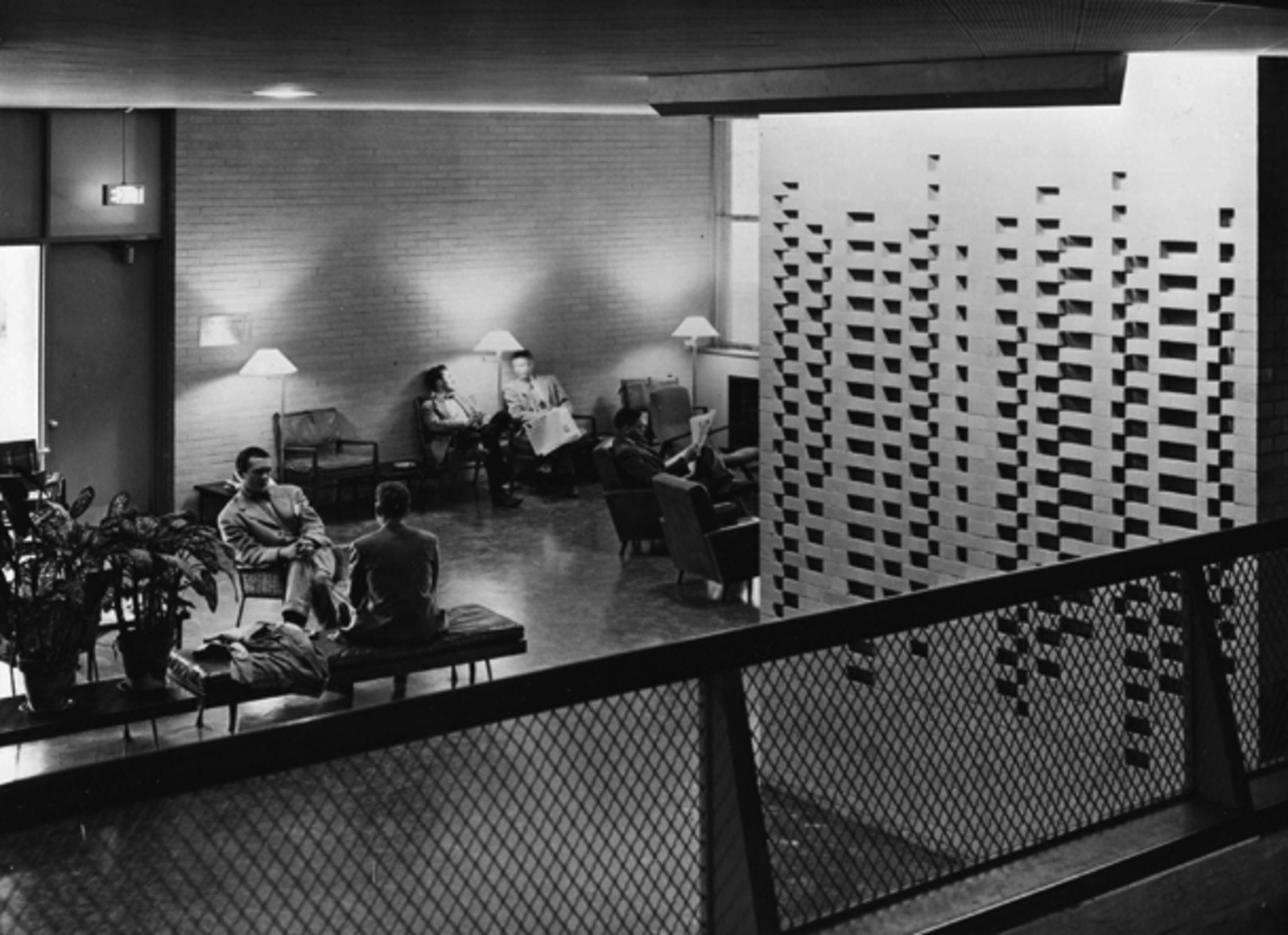

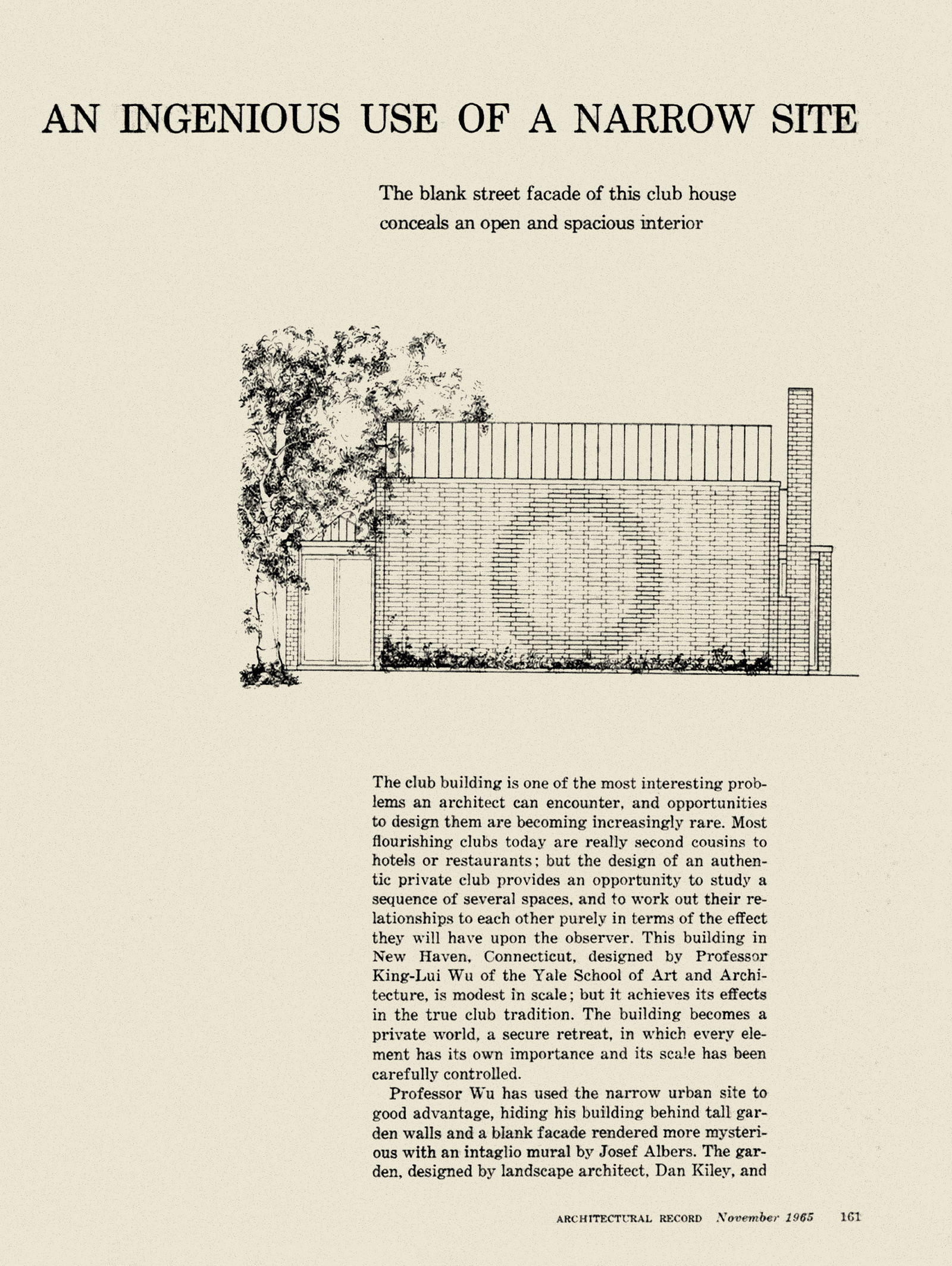

One such collaboration was for the headquarters of Manuscript, a secret society and senior club at Yale University, constructed by Wu in 1962. Manuscripts’ members, who primarily had backgrounds in the arts, wanted a modern looking clubhouse (called the “tomb”) to reflect their avant-garde outlook. Wu’s solution was a multi-level building with an open, light-filled floorplan to contrast against an understated exterior. From the street, the only visible element of the building is an unremarkable white-brick wall, upon which Wu commissioned Albers to create a mural. Perhaps in need of a break from his square studies, Albers chose the outline of a circle to adorn the facade of the building. The shape both represented the continuous bond between Manuscript members and symbolized the sun, one of the club’s secret emblems.

To apply the circle, Albers reverted back to his brick-light experiments. He suggested the clever technique of removing grout between select bricks to affect a more pronounced shadow in select areas of the wall. The circle would only be visible if the sun caught the wall at the right angle—the perfect visual for a secret tomb. In practice, however, the technique proved to be too subtle, which led Wu to paint parts of the mortar brown to create a more pronounced version of the graphic. In the final mural, the symbol remains discreet, a mark only seen by those who know where to look.

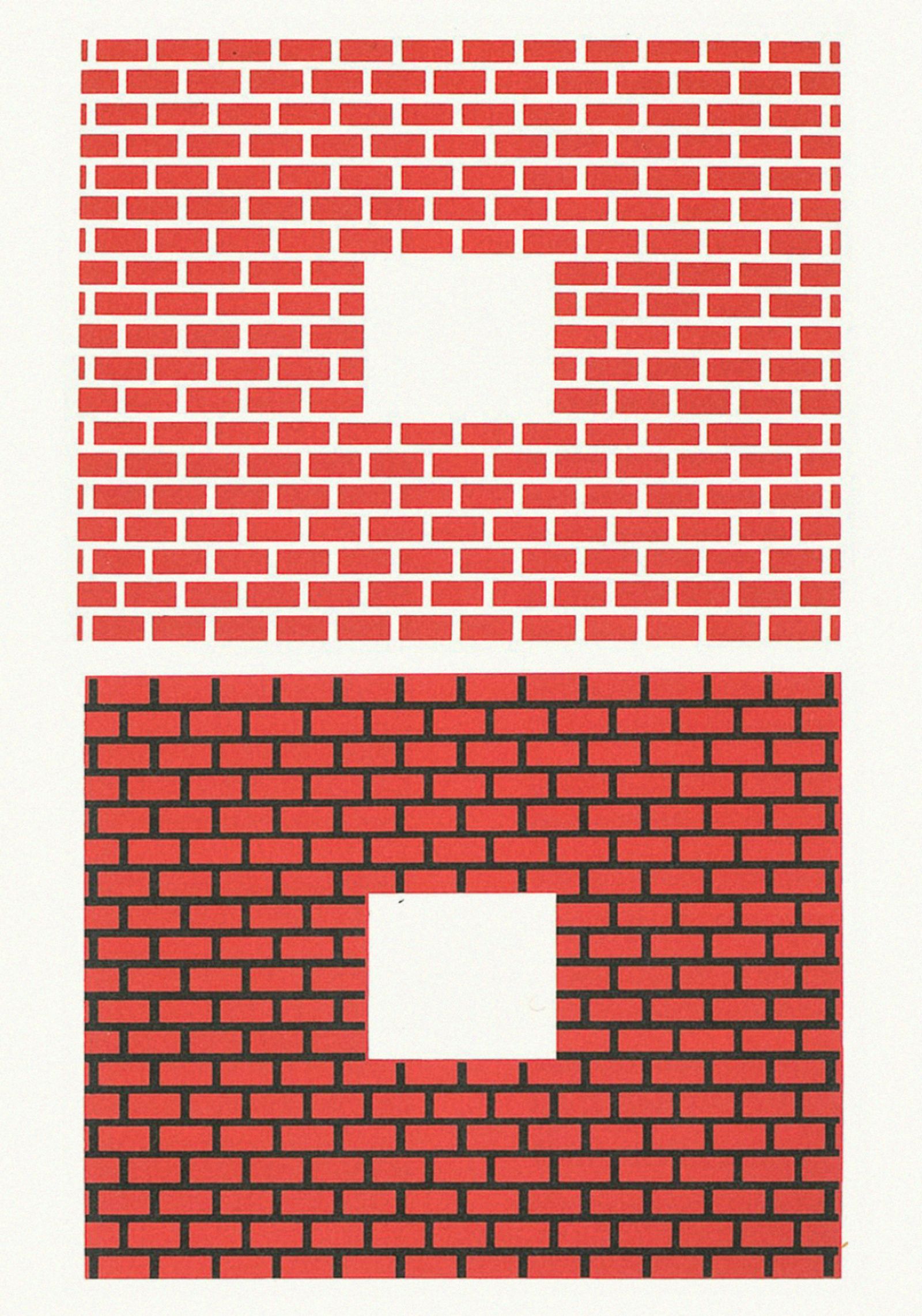

Brick study from Interaction of Color, 1963

A year later, Albers published his masterwork, Interaction of Color (1963), showing the results of his color studies. Among pages filled with squares and rectangles of various colors, is a study reminiscent of the subtle symbol for the “tomb.” Two squares on a page are filled with a graphic red-brick pattern; the square on the right shows the bricks with white mortar, while the square on the left shows the bricks inset in brown. From the volume and precision of such studies, it’s easy to characterize Albers as a fairly obsessive figure, and indeed his fixation on the square is even more evident in his attempt to deviate from the form. What is perhaps the most iconic circle in Albers’ oeuvre is nearly invisible, and what’s more, it’s composed solely of rectangles… back to square one.

Spread from Architecture Magazine (1965) describing the mural by Joseph Albers