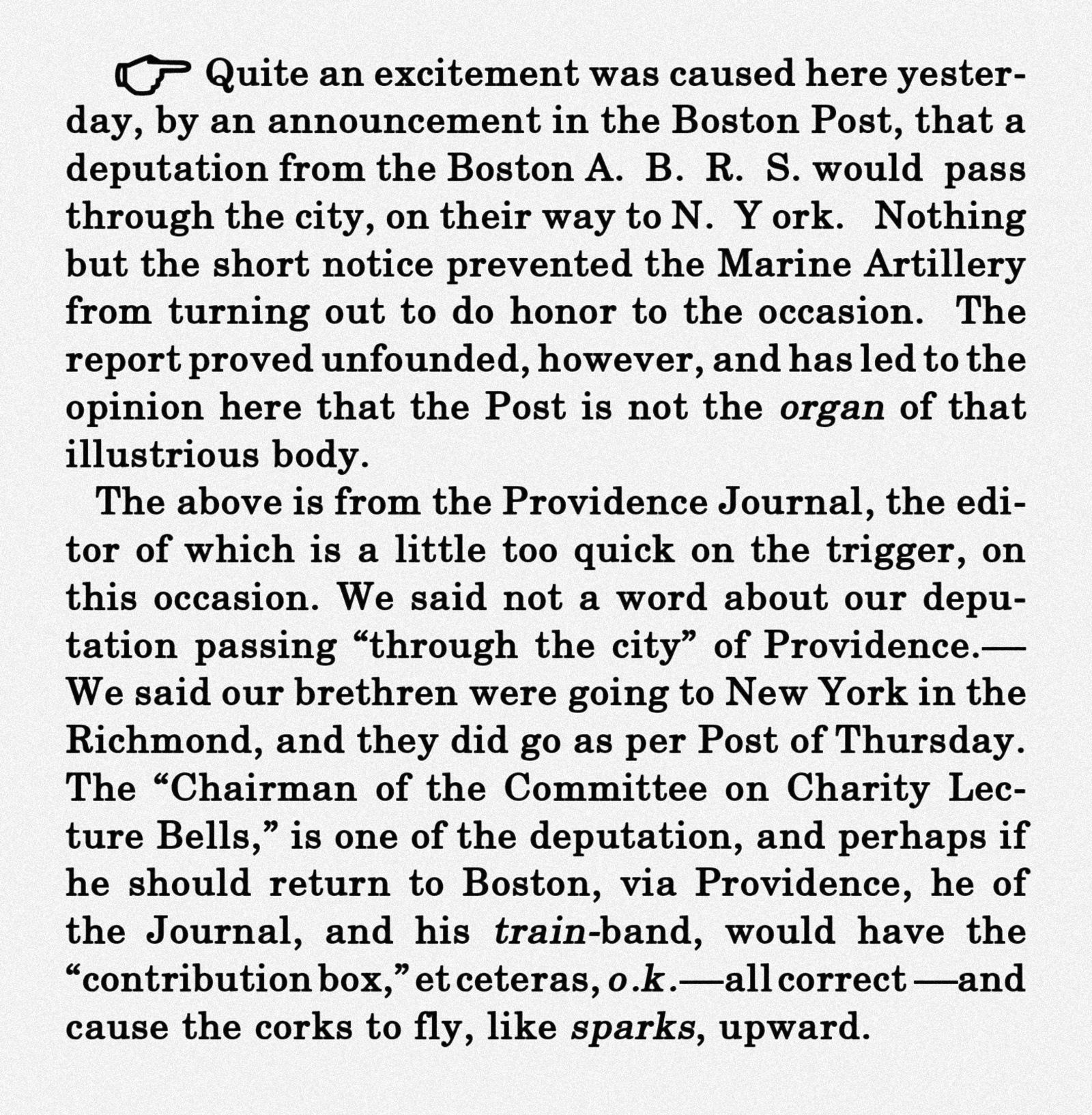

The first use of OK, discovered by Read, dates back to an inside joke in a 1839 newspaper article. But before we get into the joke, consider that at the time society was in the midst of an abbreviation craze, not totally dissimilar from the internet slang of today (SMH). Innovative and impractical abbreviations appeared daily in local newspapers (N.G./no go, G.C./gin cocktail, G.T. /gone to Texas) and at times would play with spelling or colloquialisms for an added level of humor. It was in the midst of this acronym frenzy that “o.k.” first appeared in Boston’s Morning Post on March 23, 1839.

The writer and founder of the paper, Charles Gordon Greene, abbreviated “all correct” but used a misspelling for comedic effect. The joke was that “oll korrect” became “o.k.” (or, “o.k.” was not OK).

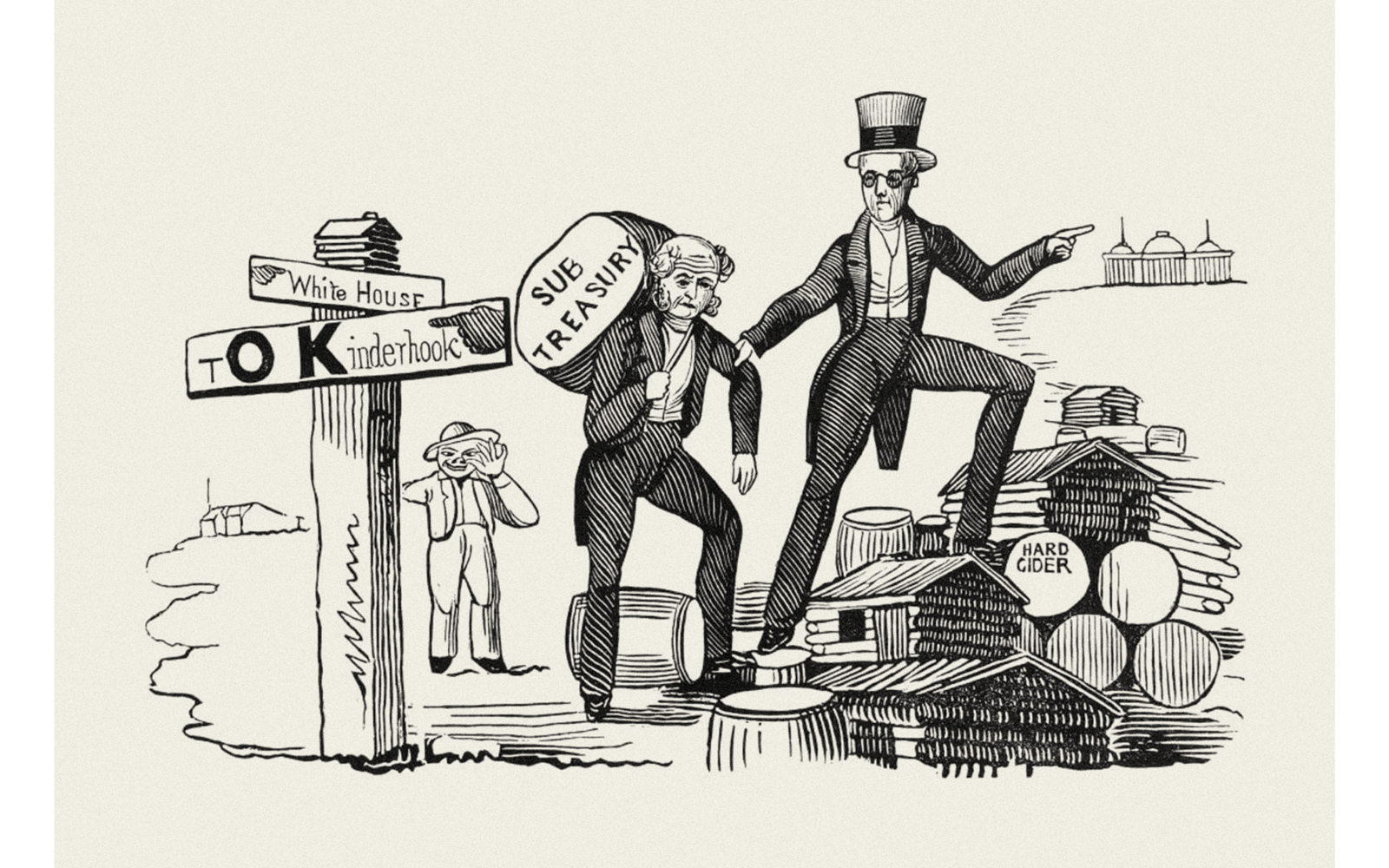

The quip might have been forgotten had it not been for the presidential election the following year. Martin Van Buren was running for a second term, and because of his age and birthplace acquired the nickname Old Kinderhook, or OK. In political campaigns it followed that a vote for Van Buren was the (k)orrect choice.

OK later played another key political role in a fake news story about former president Andrew Jackson’s reputed poor spelling, but the backstory is far too tangled to go into here. In the decades following, the abbreviation gained traction outside of the political sphere and into everyday vocabulary.

Prior to Read’s findings, the origins of OK were muddied by rumors and hearsay from an array of cultures and contexts. Although many have since been debunked, there are several theories worth revisiting if only to better understand the myth and curiosity surrounding these two simple characters.

Choctaw OK: Peter Paul and Mary sing in “All Mixed Up” that “the Choctaw gave us the word ‘okay’”, a belief that stems from the Choctaw word “okeh” meaning “it is true” or “it is so”.

0 Killed: After battles in the Civil War, troops would create posters with tallies of soldiers that were captured, killed, or alive. OK was thought to be an abbreviation for “0 killed”.

OK Fleas: The Geoponica is a collection of 20 books on agriculture written in the 10th century. In the text it is written that repeating the Greek letters Omega and Khi twice would cast a spell to repel fleas.

Despite its murky genealogy, OK became a fixture in the U.S. lexicon in the latter half of the 19th century. And what better way to demonstrate Americans’ love affair with the fashionable abbreviation than its popularity in the realms of branding and advertising.

OK, even in its earliest use as “all correct,” conveys a certain sense of utility or mediocre approval. If a meal is OK it is neither memorable nor abhorrent, a paper that is OK has no severe flaws nor any new insights, if OK were a grade it might get a solid C. It is odd, then, that OK became such a success in marketing with items like O.K. Foods, OKAY Pure Naturals hair care, OK Smile Toothpaste, or even O.K. Condoms if you feel like taking a risk…

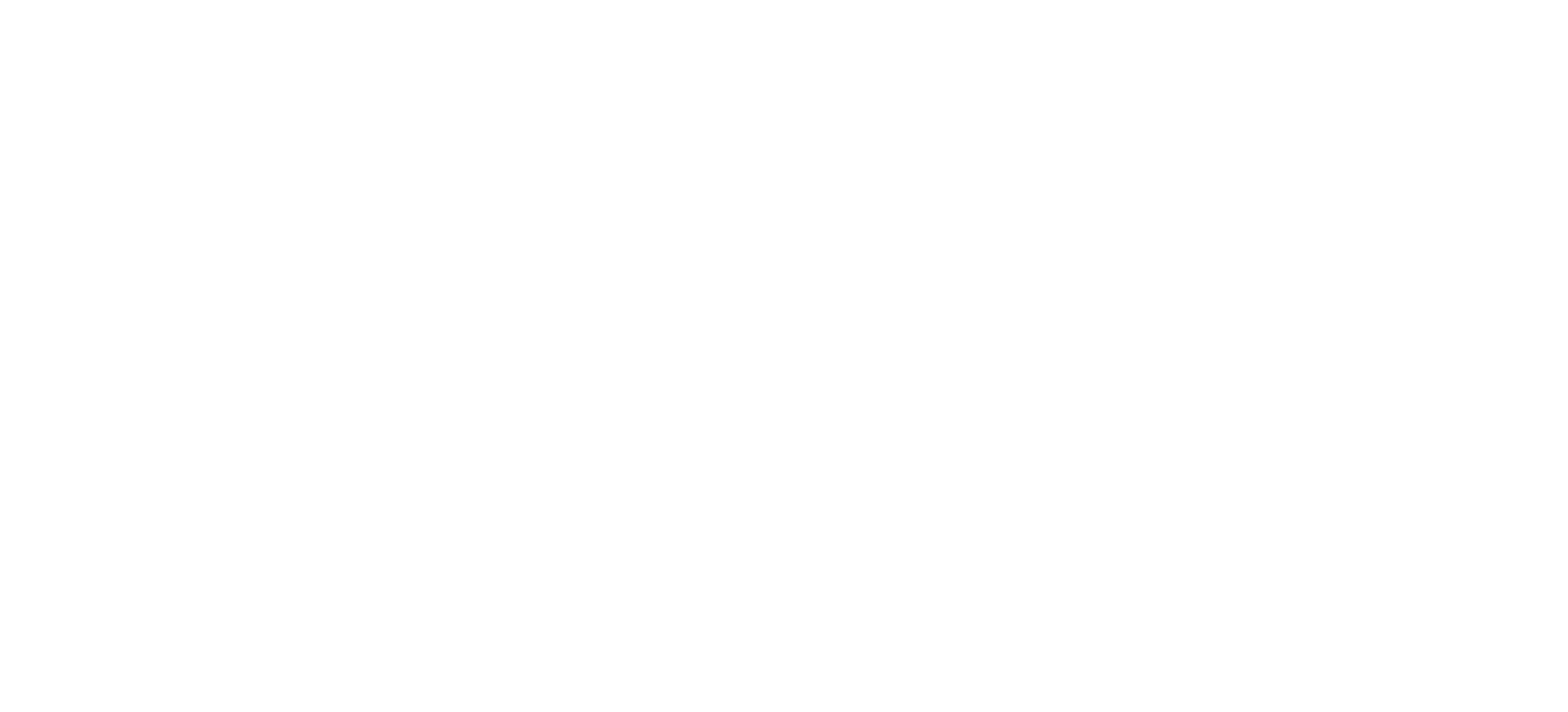

OK’s earliest use in branding was for James Pyle’s O.K. Soap (later renamed Pearline Soap) in 1852. The first line of Pyle’s obituary proudly claims that the businessman “brought O.K. to popularity.”

In the 1950s Chevy ran a large promotional campaign for their used cars centered on a seal of “OK.” Any vehicle on the lot with an OK hangtag meant the car had been checked out and approved for sale.

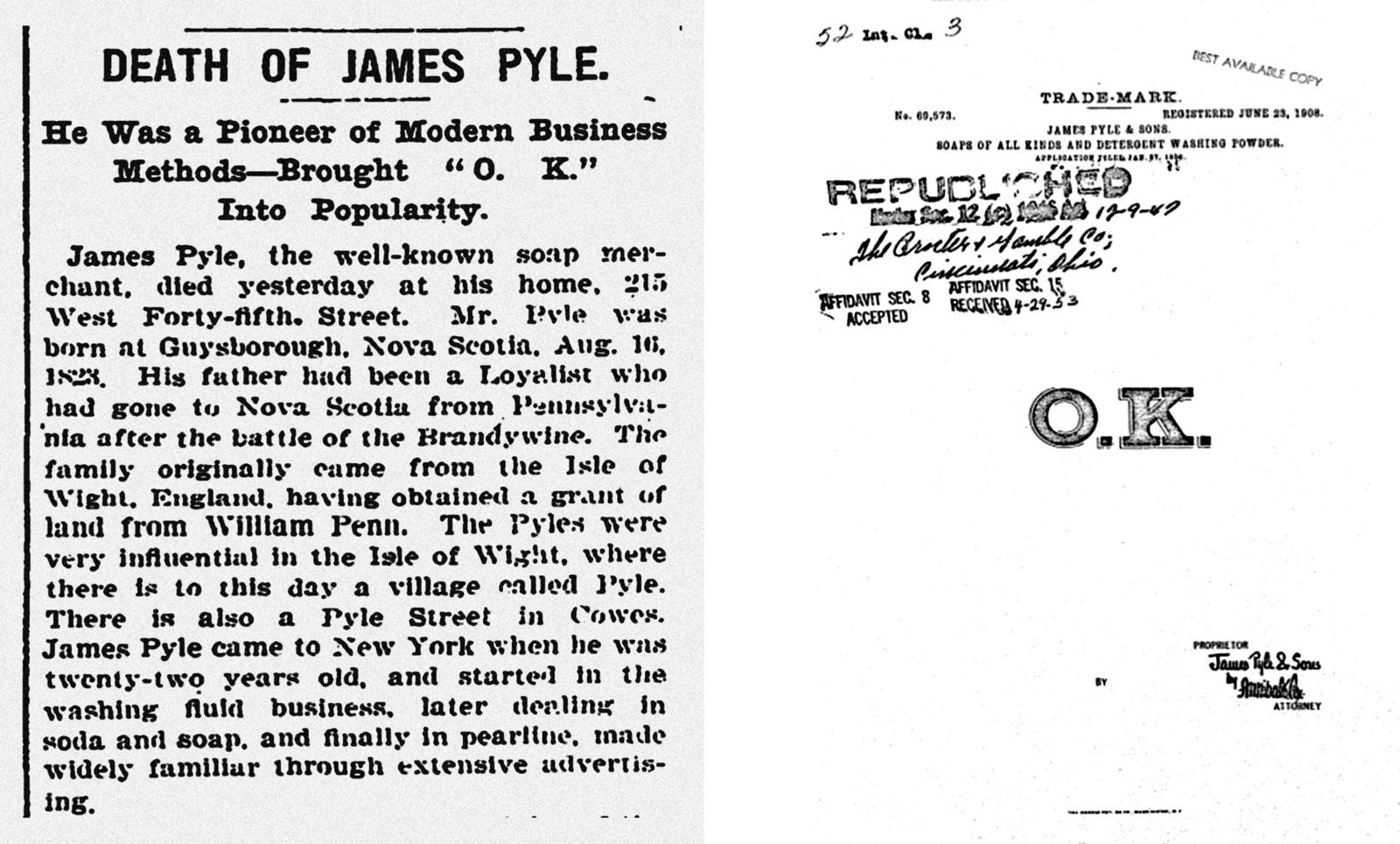

In the 1990s, researchers discovered that “Coke” was the second most recognized word in the world, bested only by “OK.” Capitalizing on the brand opportunity, Coke created OK Soda targeted towards a cynical Gen X, with an anti-advertising campaign dressed up in neo-noir design. The word OK perfectly encapsulated the mediocrity that the brand used at its selling point. In the first line of OK’s manifesto, it states: “What’s the point of OK? Well, what’s the point of anything?”

Alt-cartoonist Daniel Clowes “sold out” and illustrated the cans, but in an act of subterfuge drew a character resembling a young Charles Manson. In response to concerns, Clowes stated that none of the contracts he signed said, “Don’t put a mass murderer on the can.”

Despite its cult following, OK Soda failed in test markets and was out of production by 1995.

In 2016, governor Mary Fallin unveiled Oklahoma’s new license plate featuring the text, “Oklahoma is OK,” which quickly caught on as an unofficial motto. The slogan was met with ridicule and in 2020 was changed to “Imagine that” to convince people that Oklahoma really was much more than just OK.

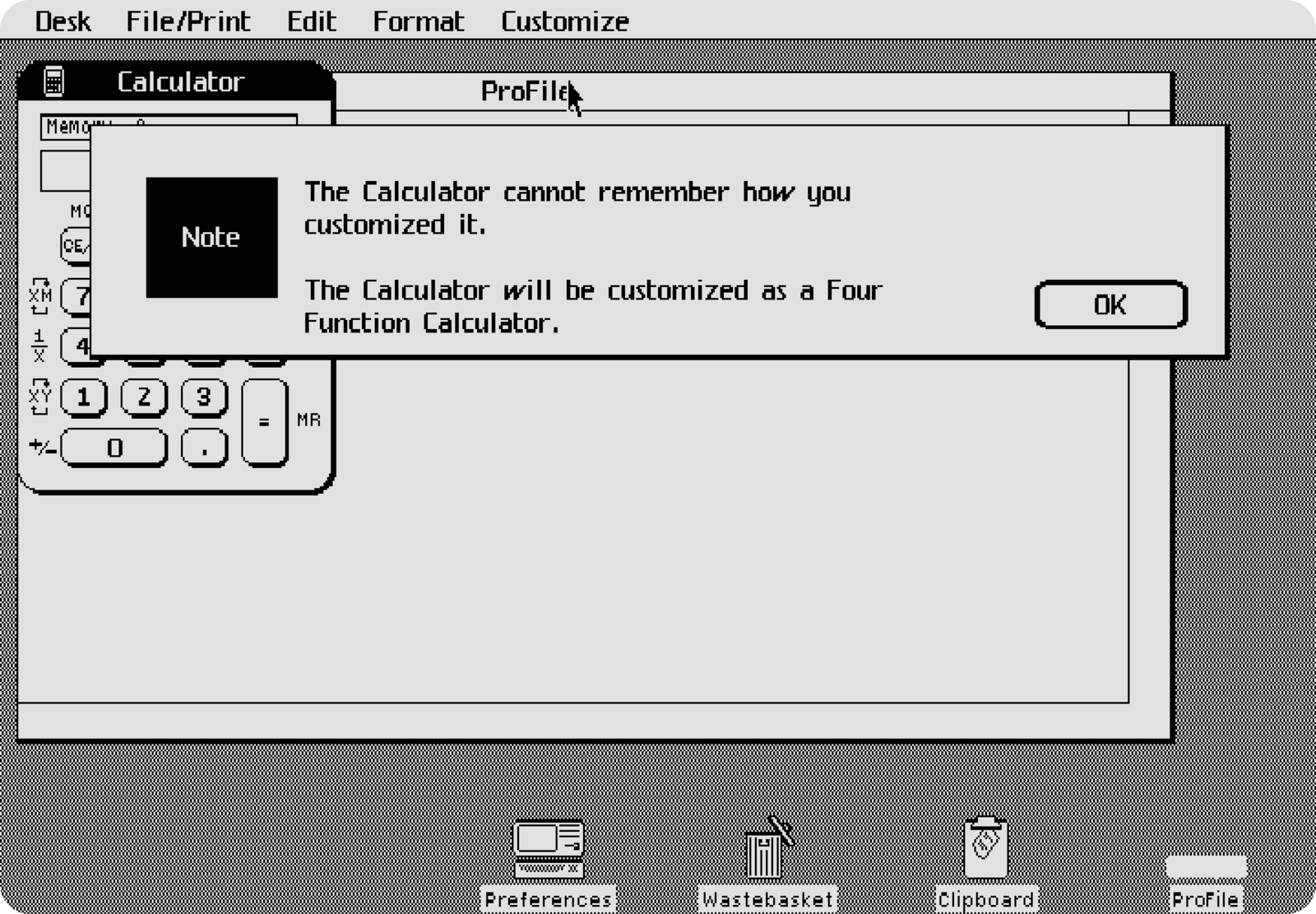

Make any decision on a device today and your two most common answers are likely to be “Cancel” and “OK.” It’s a subtle role for the abbreviation (compared to starring in a Coke or Chevy ad) yet one that feels so natural it’s hard to imagine an alternative. But as developers were creating the early interface for personal computers, “OK” wasn’t their first choice. With the Lisa computer in 1983, Apple developers originally chose “Do It” and “Cancel” as options for the new point-and-click navigation.

Manager Larry Tesler urged the team to test the software with real users who, it turned out, were confused by the “Do It” option. In fact, one user reported feeling annoyed that the computer kept calling him a “Dolt.”

Engineers had originally felt “OK” was too conversational, but circled back to the abbreviation because of its visual form, immediacy, and universal recognizability.

Today, in a linguistic world of emojis and constantly emerging iMessage abbreviations (lol, idgaf, rofl, etc.) OK remains supreme. Well, not OK, but an updated version, OK 2.0. With the simple gesture of cutting its slim form in half, the inside joke-turned-most-famous word has not only survived, but doubled its potency.

In a New Yorker review of the 2008 book Thumbspeak, Louis Menand declares “K” as likely the most common (and in my opinion, most controversial) text message. As she puts it, the single letter carries with it a powerful decree, “I have nothing to say, but God forbid that you should think that I am ignoring your message.”

Besides its practical use, K serves as a reminder of the abbreviation’s versatility. Whether with four letters (Okay), three letters (A-OK), two letters (OK), one letter (K), or no letters at all as a hand sign, OK will remain… well, OK.

Or, as crunk rap pioneer Lil’ Jon teaches us…

Okaaaaaaay!