#1: Observations on Sinistrality

Studies have shown left-handed people are more creative, have advantages in sports, and are more adept with language and communication. But operating in a world that favors the right hand comes with its own set of challenges, the severity of which has varied throughout history. In the Middle Ages for example, left-handed individuals were prosecuted for witchcraft. Still today, tools and technology are often developed with righties in mind. Understanding Left Handedness is an ongoing column by left-handed typographer Phaedra Charles that uses a relatively simple bias to uncover the ways discrimination can be hidden in the design process.

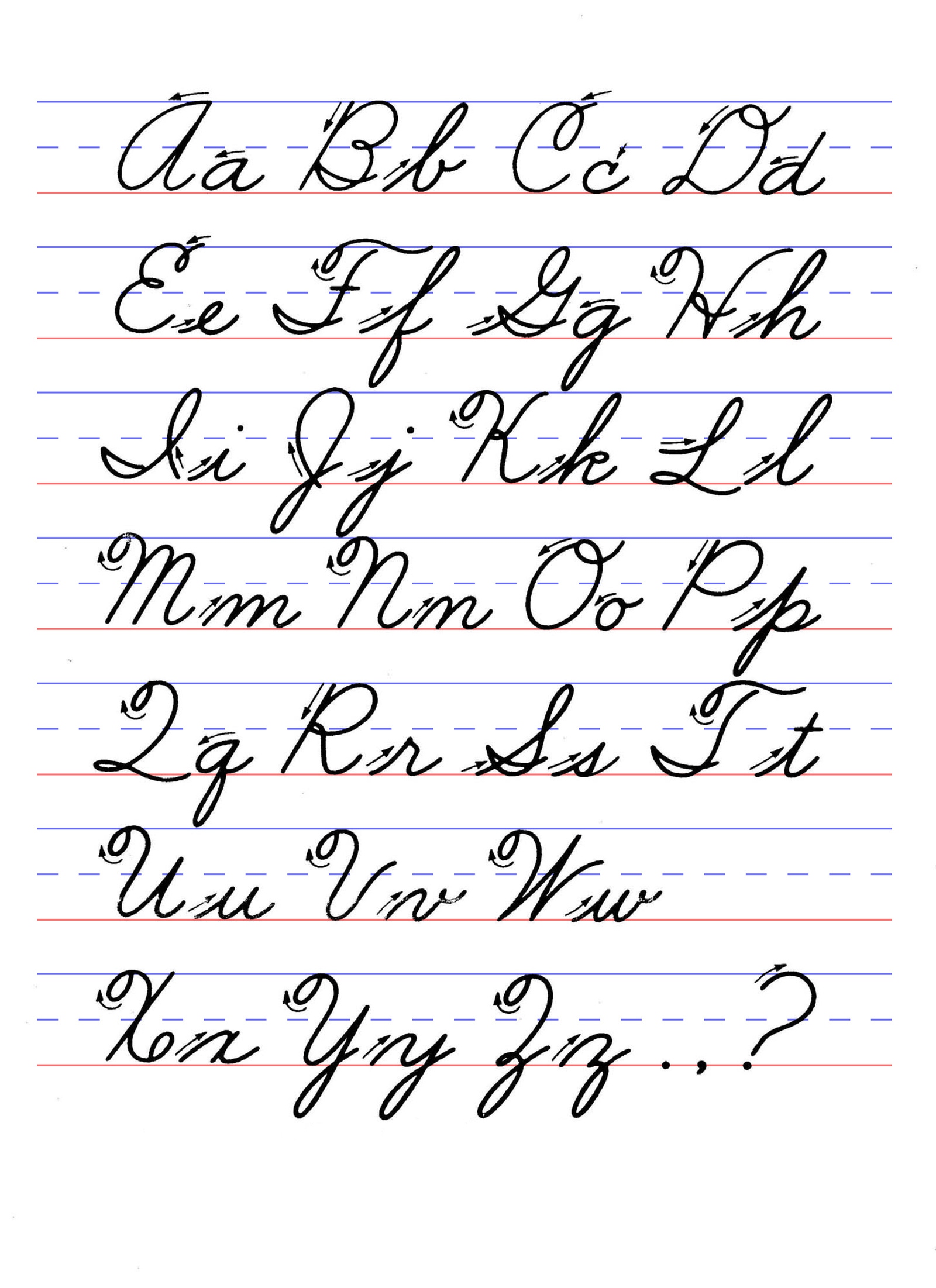

My earliest memory of becoming conscious of my “otherness” came in elementary school while learning the Zaner-Bloser cursive handwriting style. We were required to write with a soft graphite pencil, and as I wrote, my hand would smudge the writing that preceded it. When I looked around at my peer’s work, I found no one else had this issue. The only piece of feedback my teacher offered was that my writing was “sloppy,” never how I might avoid this. My teacher’s inability to offer adequate feedback derived from a failure to understand that I was left-handed and thus would need different instruction from my fellow right-handed classmates. Since this experience, I have been interested in exploring the left-hand bias of calligraphy instruction.

This frustration, of feeling different but having no language to speak of it, extended beyond handwriting. Playing any schoolyard game would often involve high-fiving my classmates. People with a right-handed dominance will instinctively high-five with their right hand. This seemingly simple social interaction is an unconscious, but coordinated effort. Much like a dance, it requires a reciprocal movement. Part of the high-five is reaching forward and across the body, to meet the other person’s right hand. If a left-handed person instinctively attempts to use their left hand, the high-five suddenly becomes something like an unexpected “patty-cake”, mirroring the actions of the other person. This mirroring throws each person off, because they are not accustomed to this form of “high-fiving.” Left-handed people learn to conform to right-hand dominated social interactions such as these, after experiencing the discomfort and confusion of trying to use their own dominant hand.

Famous left-hander Barack Obama

Why am I left-handed? I began asking this question intently in 2016, when I began attending the Type@Cooper type design program at the Cooper Union. Specifically, I was very interested in why calligraphy instruction tended to disregard the left-handed experience.

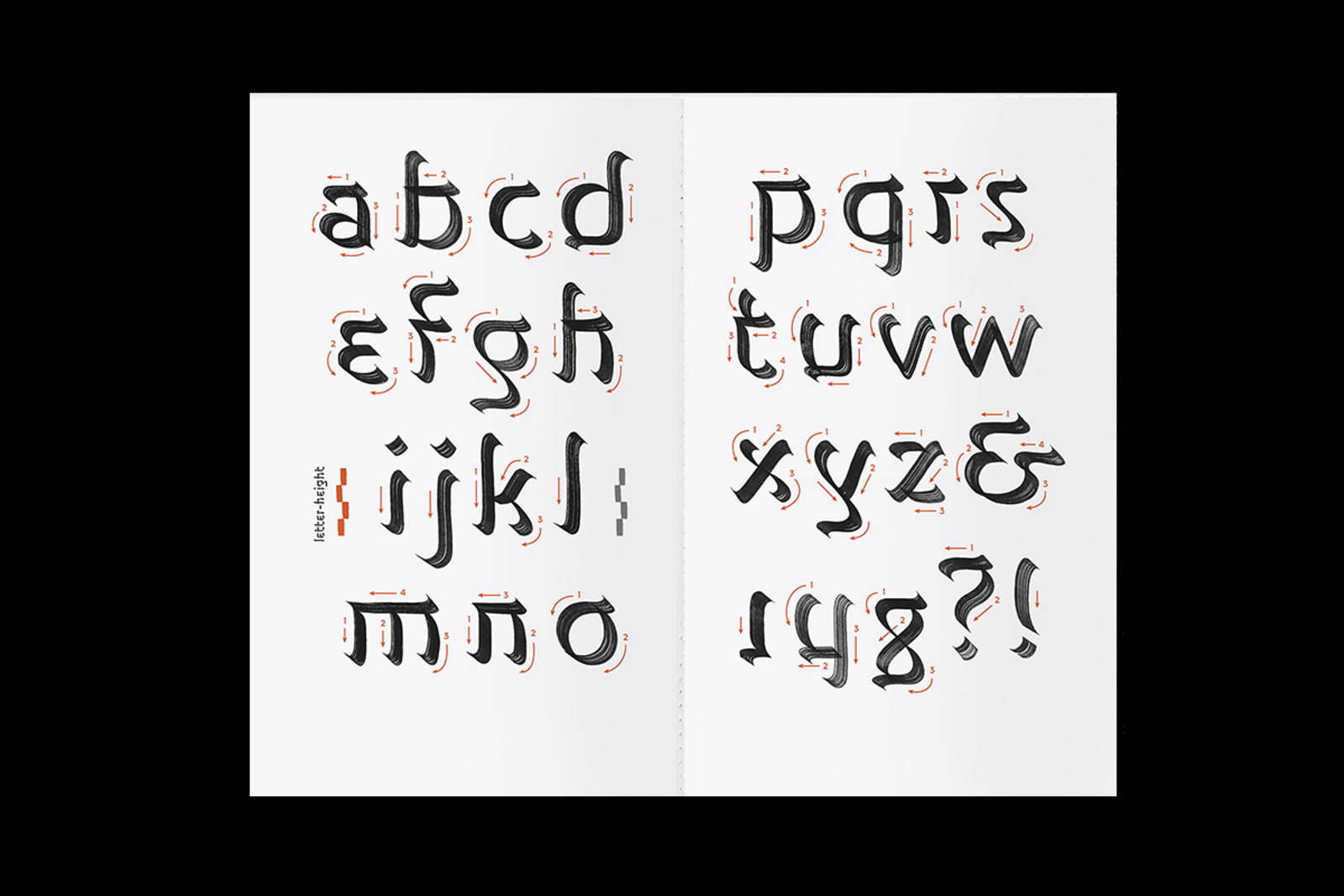

Attending the program, and making a concerted effort to practice calligraphy, made me acutely aware of the right-handed bias that is inherent to the process of letterforming. Seeing this bias, I had the idea to deconstruct the alphabet and to create forms oriented more comfortably toward left-handed movement using a broad-edged writing tool. This writing system I called “Sinistral Hand.” Drawing inspiration fromt other writing systems (such as Hebrew and Devanagari) where the direction of writing or angle of the pen mirrors the Latin alphabet, served as inspiration for how the ductus of a left-handed writing system could work.

I translated more of these ideas into a brush script typeface, Mollydooker. Even though a left-handed person using a pointed brush matches the angle of writing used by a right-handed person with a broad-edged writing tool, the pattern of writing is quite different, and this difference allows for new and innovative approaches that a right-handed person would find much more difficult to achieve. For example, as shown in my typeface Mollydooker, a backward leaning script is the logical mirror of a forward-leaning script.

Zaner-Bloser cursive handwriting instructions

Spread from A Guide to Sinistral Hand by Phaedra Charles

I believe it’s worth exploring these approaches not just for their aesthetic value, but also as a means of creating a broader, more inclusive education surrounding letterforming in calligraphy, lettering, and type design. The implications of shining a light on a previously marginalized group of writers can have a profound impact on validating their experience. The Cooper Union conducted a fantastic case study of how they redesigned their bathroom signage to be more inclusive of non-conforming gender identities. This case study is a great example of how design systems that have previously been seen as immutable can be reshaped with a new understanding of the fallacy of the gender binary. As a non-binary transwoman who has visited this institution often, it’s had a profound impact on my own personal experience of feeling seen, feeling validated, and feeling safe. It has shown me the possibility of a world in which a person like me is welcome.

Anyone that comes from a non-conforming culture or group, whether represented by physical ability, gender, sexuality, or race, understands the harm of conforming to “pass.” The impact of handedness is far less damaging and disadvantageous than what these other groups experience, but still worth exploring and understanding. There are times in human history where left-handedness may not have been regarded in such a benign way, such as when left-handed children were physically disciplined or punished for using their dominant hand. Forced handedness has been shown in research to give rise to a host of other learning disabilities. During medieval times, more severe forms of punishment and ostracization occurred when left-handedness was used in trials as evidence of witchcraft.

Again, left-handed people do not face the same level of institutional discrimination and marginalization other groups have faced. But maybe, through its relatively uncomplicated material reality, designing for left-handedness can give students and designers alike a playground for beginning to understand the ways that design often, if not always, engenders bias against those with a social or physical disability.

Throughout this series, I will examine the relationship of handedness to handwriting and calligraphy, as well as to social customs, activities, and attitudes that have had a profound impact on the ways that left-handed people have adapted to live in a right-handed world. And I will return to the question that has continued to perplex me, and has remained unanswered throughout all my research: why am I left-handed?

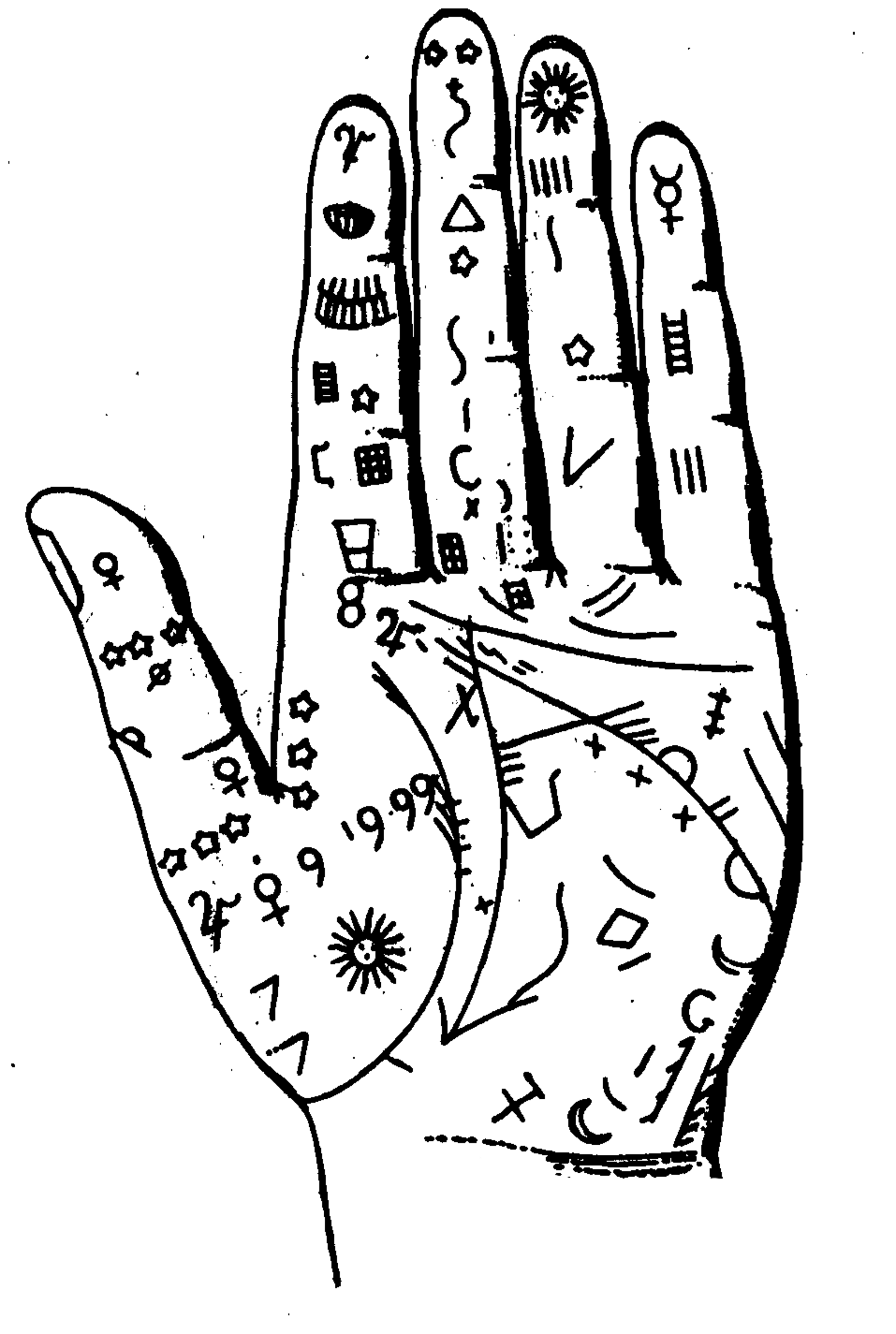

Diagram of the Left Hand, from ‘Oeuvres Diverses’ by Jean Belot, 1649