The Sphinx, A Living Image

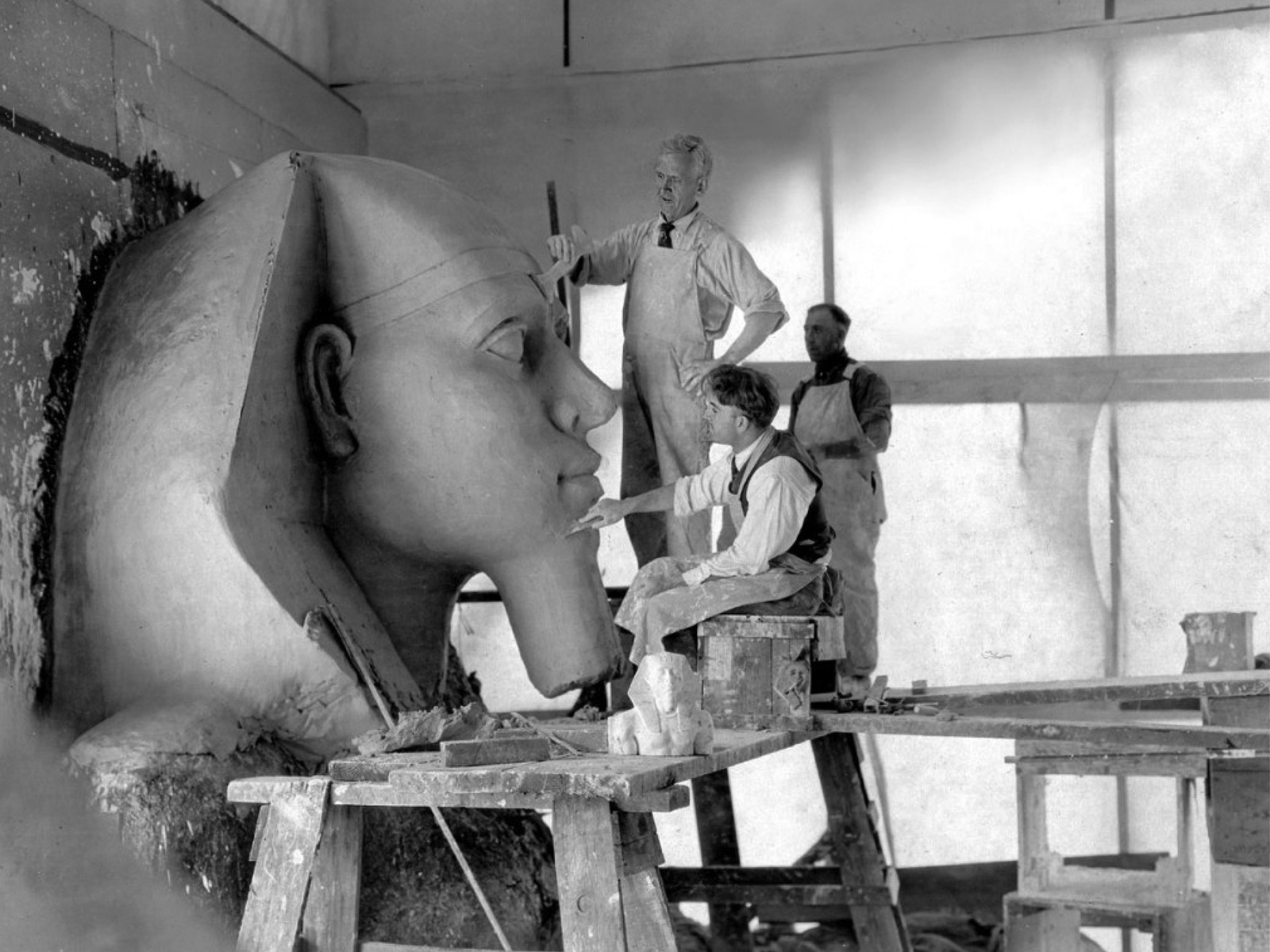

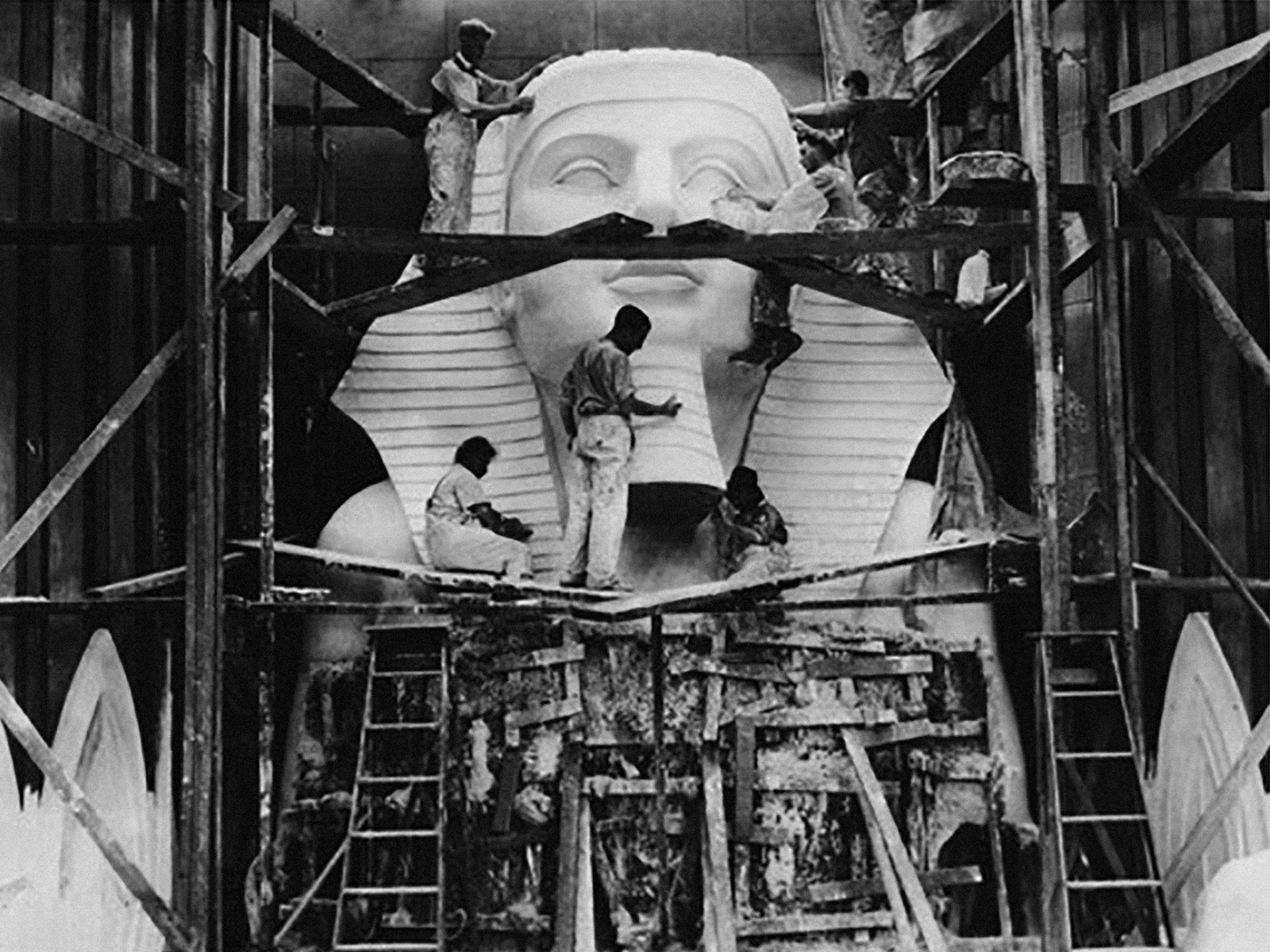

The Ten Commandments, Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 film about the life of Moses, opens with the hazy image of a sphinx’s head. One of the Pharaoh’s workers standing in front of, or possibly on the sphinx’s feet, whips those below, who are tasked with pulling the statue from one side of the temple to the other. The film tells the story of the Israelites’ flight from the City of the Pharaoh across the Red Sea. But what appears to be Ancient Egypt, a vast desert littered with monuments, pyramids, and carved sphinxes, is actually an elaborate set built on a ten-dollar plot of land in California. Filming in Egypt would have been too expensive, so instead DeMille commissioned French Art Nouveau designer Paul Iribe to create the set. Comprising a 36-story temple, four Pharaoh statues each standing over 30 feet tall, and 21 sphinxes, it was a complicated build involving over 1000 workers, and a vastly exceeded budget of over 1 million. When filming wrapped, and moving the set proved impossible, rumor has it that DeMille ordered it be “dynamited” and buried under the Guadalupe-Nipomo dunes.

Set production for The Ten Commandments (1923)

Set production for The Ten Commandments (1923)

Set production for The Ten Commandments (1923)

A lion with the wings of an eagle and the head of a woman, a falcon, a cat, or a sheep; or a wingless figure with the body of a lion and the head of a pharaoh, the sphinx sits at entrances guarding temples, monuments, cities, palaces, hotels, and golf courses. It symbolizes at once royalty and sacred status, vengeance, guardianship, and shrewdness. In Ancient Egypt, the sphinx was a representation of the Sun God, Horus. In Greek mythology, the sphinx confronted those passing the rocks outside the city of Thebes, and devoured anyone who couldn’t answer the riddle: “What goes on four feet in the morning, two feet in midday, and three feet in the evening?”

The word “sphinx” is thought to come from the verb “to squeeze” in Ancient Greek, stemming from the strangulation that would result from failure to solve the riddle. It is also thought to be a Greek corruption of the Egyptian word “shesepankh,” meaning “living image” in reference to the stone the form is carved from, the living rock—or bedrock—and the sphinx being the living image of the Gods. The living image might be in reference to being cast in the same mould as, or in the spitting image of another. It may also refer to an image that continuously shifts shape and meaning, accruing new myth and legend around it as it continues to be built upon both structurally and metaphorically. The sphinx, the living image, lends itself to repeated reinvention, an unsanctioned reproduction, a bootleg ascribed to no one that holds its own layered riddle in its form.

Greek statue of sphinx (6th century BCE)

Various civilizations have deployed the sphinx to evoke feelings of comfort and fear, reverence, and to display strength and wonder. Ancient sphinx traveled from Egypt to Greece along trade routes, showing up in Indian mythology (a guardian over gateways and doors warding off evil and relieving people of their sins), adorning monuments and the bells of pagodas in Thailand and Myanmar, appearing again as a symbol of guardianship during the Renaissance—with breasts, pearls, and an elaborate hairdo—as well as being adopted into fountains with water pouring out of its mouth, as if it is dribbling, or throwing up. Sphinxs cropped up in the paintings and literature of the Decadent movement, which was characterized by an aesthetic of excess and fantasy, with one appearing as a femme fatale, trying to seduce Oedipus in Gustave Moreau’s 1864 painting. In Victorian England, Oscar Wilde took a similar view in his poem, The Sphinx, with the titular character described as a ‘murderess’ of those she desires, defeated only by the abstinence of a Christian man— “Come forth you exquisite grotesque! half woman and half animal!”

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864)

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014)

Since the turn of the 20th century, sphinxes have continued to find places to sit, appearing outside temples, guarding monuments, casinos, department store atriums, and in works of art. In Riddles of the Sphinx, a 1977 experimental film by Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, the myth of Oedipus’ encounter with the sphinx punctuates a series of chapters examining the role of the mother, and the inner and outward negotiations required to navigate domestic life. In 2014, Kara Walker’s monumental A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby was installed at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, featuring a close to 80-foot long, sugar-coated sphinx hybrid evoking the Southern Mammy archetype in “homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our sweet tastes.” The work took the form of a sphinx as Walker realized the need for a monument that was recognisable and loaded, capable of holding multiple meanings. A variously appropriated and reproduced image with its roots in Africa, here applied with the image of a White American stereotype of a Black enslaved woman.

Laura Mulvey & Peter Wollen, still from Riddles of the Sphinx (1977)

In 2023, on the roof of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lauren Halsey installed a temple flanked by four sphinxes, each with the face of a family member. Along with columns that bear portraits of artist friends, there are wall inscriptions of signage for grassroots organizations, statements of protest, and affirmations, the work forming an archive of Black popular culture in South Central L.A. The installation references the structure of the Temple of Dendur—built in Roman Egypt in 10 BCE, and “given” to The Met in 1963, which is decorated with elaborate relief carvings of goddesses and gods. Here, the tomb inscribed with the Book of the Dead becomes a dynamic record of everyday life, with the structure opened out for people to walk through and interact with.

Lauren Halsey, the eastside of south central los angeles hieroglyph prototype architecture (I) (2013)

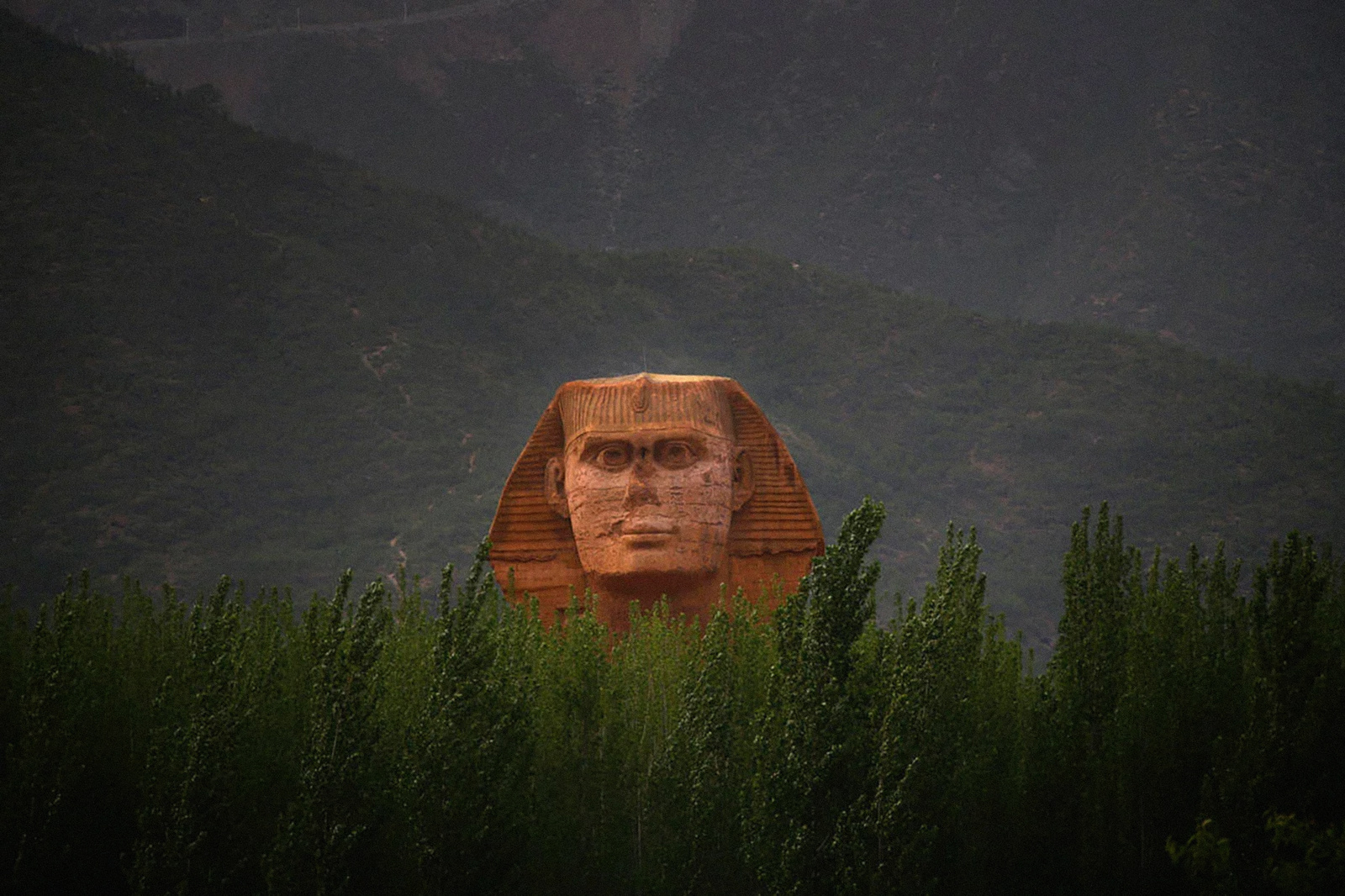

Sphinx replica in Shijiazhuang, China

Replica sphinx in Shijiazhuang, China

Sphinx replica in Shandong, China

Gifted, stolen, recreated, dynamited, real or fake, the sphinx lives many lives. Ancient Egyptian monuments have been mimicked in European architecture since the Renaissance, in tandem with British and French imperial plundering projects. Since the early 2000s, there have been repeated sightings of sphinx of Giza across China. One in the Lanzhou Silk Road Cultural Relics Park, which also has a full-size Parthenon; one in Anhui province, its head painted in blue and gold, with drawn-on eyebrows; a snow replica built for a “snow sculpture” expo; as well as one in Hebei province, said to have been built for filming purposes. The Hebei sphinx was beheaded after Egypt complained to UNESCO that it was a violation of intellectual property and received too many visitors. But a few years later, the head was reattached. The Great Sphinx of Hebei continues to watch from its perch.

Egyptian Revival architecture lives at Harrods, London’s luxury department store. Commissioned by its then-owner, Egyptian businessman Mohamed Al-Fayed in 1992, the Egyptian Escalator was designed by artist William Mitchell and includes more than a dozen sphinxes in stone and gold, each bearing Al-Fayed’s likeness (a spitting image). In the Egyptian Hall, you are greeted by an imposing gold sphinx, and as you ascend the escalator, you pass another gold sphinx form with the body of a kneeling woman. Sphinx-like heads top columns, the undersides of the escalators hold bas reliefs of the goddess Isis, ruler of the world; and a stone sphinx perches on a plinth, its paws resting on the Harrods building. It is the most imposing versions of the sphinx that carry the likeness of Al-Fayed, who once noted: “It’s a listed monument, so they can’t take me away, they can’t.” Al-Fayed’s use of the sphinx as an image of strength and reverence, from his own history and deployed at the heart of the British Empire, is a fitting display of its potential as a living image meant for riddles and reproduction.

Sphinx with the face of Mohamed al Fayed in Harrod’s, London

Replica of the Sphinx outside of the Luxor Hotel, Las Vegas

In Las Vegas, the casino hotel Luxor, developed by Circus Circus Enterprises in 1993, is a black glass pyramid fronted by a sphinx mimicking the Great Sphinx of Giza. Its body is the resort’s porte-cochère, and when the casino hotel opened there was a “Karnak Lake” at its feet, with computer-controlled fountains synchronized with lasers that shot out from the eyes of the sphinx, but it is now a car park. While the sphinxes of Harrods aspire to immortality, making a myth of a man, the sphinx at Luxor is a sort-of non-denominational nod to the imposing scale of religious structures, lending an atmosphere of legacy to a brand new building.

When Luxor Las Vegas first opened, Circus Circus worked with Egyptologists in developing the theme, installing fiberglass and plaster replicas of Egyptian artifacts that could be viewed from an indoor “Nile River” boat ride. They wanted to give the casino hotel an air of high culture, inviting guests to enjoy a side of “museum” as they tried their luck on the slots. Luxor’s pyramid is three quarters of the size of the Great Pyramid of Giza, which for 3800 years stood as the world’s tallest built structure, and is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the World. The Great Pyramid of Luxor, Las Vegas is topped with the world’s most powerful light, 42.3 billion candela—basically 42.3 billion wax candles—which can be seen from space.

Sky beam of the Luxor hotel, the brightest light in the world

But invoking the living image of the sphinx seems to have invoked some other spirits. Thanks to the number of murders, suicides, and unexplained deaths at Luxor, Las Vegas, rumor has it that the single sphinx in front of the glass pyramid has cursed the casino hotel, and made it more haunted than any other place on the strip. “Ghostcitytours.com” lists rooms and their paranormal activities including “The Poltergeist Room,” multiple rooms haunted by “The Deadly Blonde,” and a ghost said to strangle guests à la the sphinx herself.

As the hotel has changed hands and undergone renovations, the Egyptian theme has become diluted—King Tut’s Tomb has been replaced with “Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition”—but throughout it all, the sphinx, its face painted like that of a mummy with blue and gold-striped hair has remained. The hotel’s MGM president has asserted: “We’re not a British museum with ancient artifacts, we’re a casino-resort,” distancing himself from the casino hotel’s original take, and the actually pretty aligned approaches of the Las Vegas strip and mega museums.

Valet at the opening of the Luxor, Las Vegas (1993)

In the summer of 2012, I ended up on Guadalupe Street, where DeMille filmed The Ten Commandments, stopping in the city with self-proclaimed “small town charm” when my friend and I detoured on a cliché road trip down Highway 1. We walked into the NAPA Auto Parts shop, drawn in by a chaotic mix of tools, wires, car exhausts, sombreros, and what looked like a Plaster of Paris foot and a chariot. The proprietor of the shop, John Perry, one of the original Beach Boys (or so he said), and a custodian of Guadalupe’s history, told us that the foot had belonged to a sphinx found buried under the nearby dunes. Locals had been digging pieces out from the sand for decades—including two sphinx heads that now had pride of place on a nearby golf course.

Remnants of the Sphinx from Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1923) unearthed in California (2017)

The set of The Ten Commandments remained unknown to anyone outside the local area until the 1980s when a group of film nerds set out on an expedition, having read in DeMille’s autobiography: “If, 1,000 years from now, archaeologists happen to dig beneath the sands of Guadalupe… I hope they will not rush into print with the amazing news that Egyptian civilization… extended all the way to the Pacific Coast of North America…”

What was built as the set of a fictional city has gone from the realm of Hollywood lore to what is now a protected historical site with archaeologists digging beneath the sands of Guadalupe in hopes of uncovering some of cinema’s past. While no one is convinced that Egyptian civilization extended to the Pacific Coast, the sphinx’s living image, and its lost city, still animates the landscape.